The Philosophy Of Photography

Ever looked at a photo and felt a strong, hard-to-explain emotion? You’re not alone. Roland Barthes, a philosopher, believed great photos could deeply affect us. This article explores why he thought photos have this power.

Before Barthes, people saw photography as a tool to capture events or subjects. Critics analyzed photos based on what they depicted and their technical aspects. Barthes, in his 1980 book “Camera Lucida,” asked a crucial question: What is the essence of photography?

Barthes started by explaining what makes photography different from other arts. Unlike painting, which interprets reality, photography mechanically captures it. It’s a direct reproduction of reality, making it distinct from painting, film, or literature.

Barthes also noted that photography lacks a code. In novels, words represent objects, people, or events, allowing for multiple interpretations. In contrast, a photograph is a direct copy of reality, leaving no room for varied interpretations.

If Barthes had stopped here, it would mean photos have no inherent meaning—they’re just mirrors of reality. This would diminish photography as an art form. However, Barthes proposed a solution. He argued that the lack of a code becomes the code of photography. The photographed object is real, and this reality gives photos a unique quality: they capture what has been.

When we pose for a photo, Barthes says we experience ourselves in four ways: how we think we are, how we want others to see us, how the photographer sees us, and how the photographer uses us for art. This makes us feel somewhat inauthentic, like experiencing a small identity crisis—a “micro-version of death.”

For viewers, there are two elements in a photo: the studium and the punctum. The studium is the cultural knowledge that allows us to understand a photo’s intentions and implications. It appeals to the intellect and operates at two levels: the denoted (what’s captured) and the connoted (symbolic meaning).

The punctum, on the other hand, is accidental—something the photographer didn’t intend. It “stings” or “wounds” and appeals to emotions. Examples range from unkempt fingernails to unexpected details that provoke a deeper emotional response. Barthes argued that the punctum exists independently of the spectator yet requires them. It’s the photographer’s unintentional gift to the viewer.

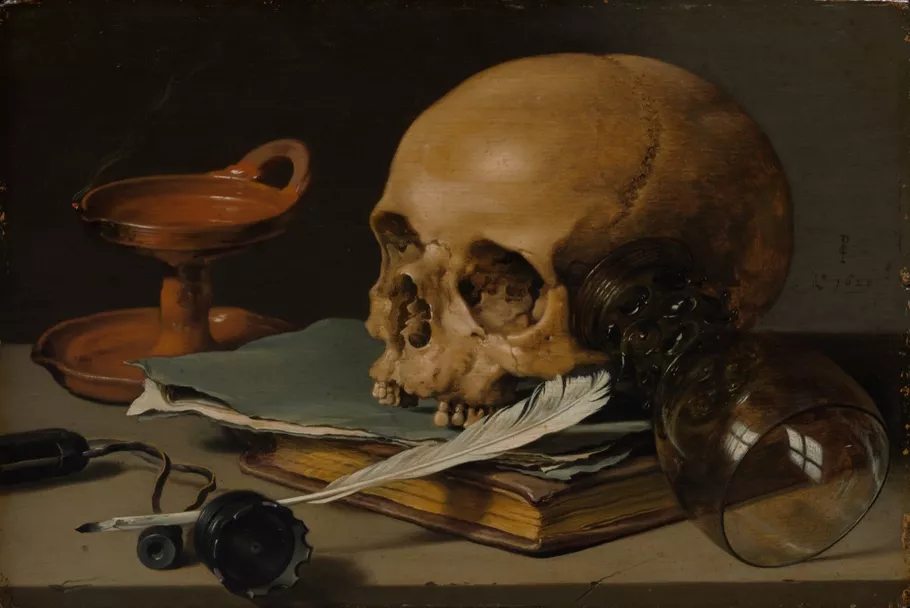

In the second part of “Camera Lucida,” Barthes introduced a new variation of punctum: time itself. Photos freeze moments in time, embodying past, present, and future. This intersection of time implies death and adds an extra layer of emotion to photos.

In conclusion, according to Barthes, photos wound us by capturing accidental details and embodying the relentless nature of time and the inevitability of death. The next time you’re moved by a photo, remember Barthes’ concepts of studium and punctum to better understand that indescribable feeling.