The Secrets Of Desire

Jacques Lacan, a French philosopher and psychoanalyst, delves into the intricate aspects of desire and pleasure, challenging conventional understandings. He contends that desire doesn’t straightforwardly aim for what it appears to seek. While it may seem that we desire complete satisfaction, Lacan argues that this is an illusion, as attaining total satisfaction is inherently impossible. This impossibility becomes a cornerstone of Lacan’s philosophical framework.

Despite the elusive nature of achieving complete satisfaction, Lacan posits that desire remains an immensely potent force in human experience. He introduces the concept of fantasy, suggesting that the pleasure associated with desire arises from the belief that the desired object is within reach. Even when desire seems directed toward tangible goals, such as a romantic relationship, the actual attainment falls short of satisfying the underlying and unattainable drive for love.

The paradoxical structure of desire, wherein it seeks perpetuation rather than cessation, can be traced back to the infant’s early trauma during the initial encounter with the Other, often symbolized by the mother. The impossibility of returning to a state of reassurance and satisfaction haunts desire throughout an individual’s life.

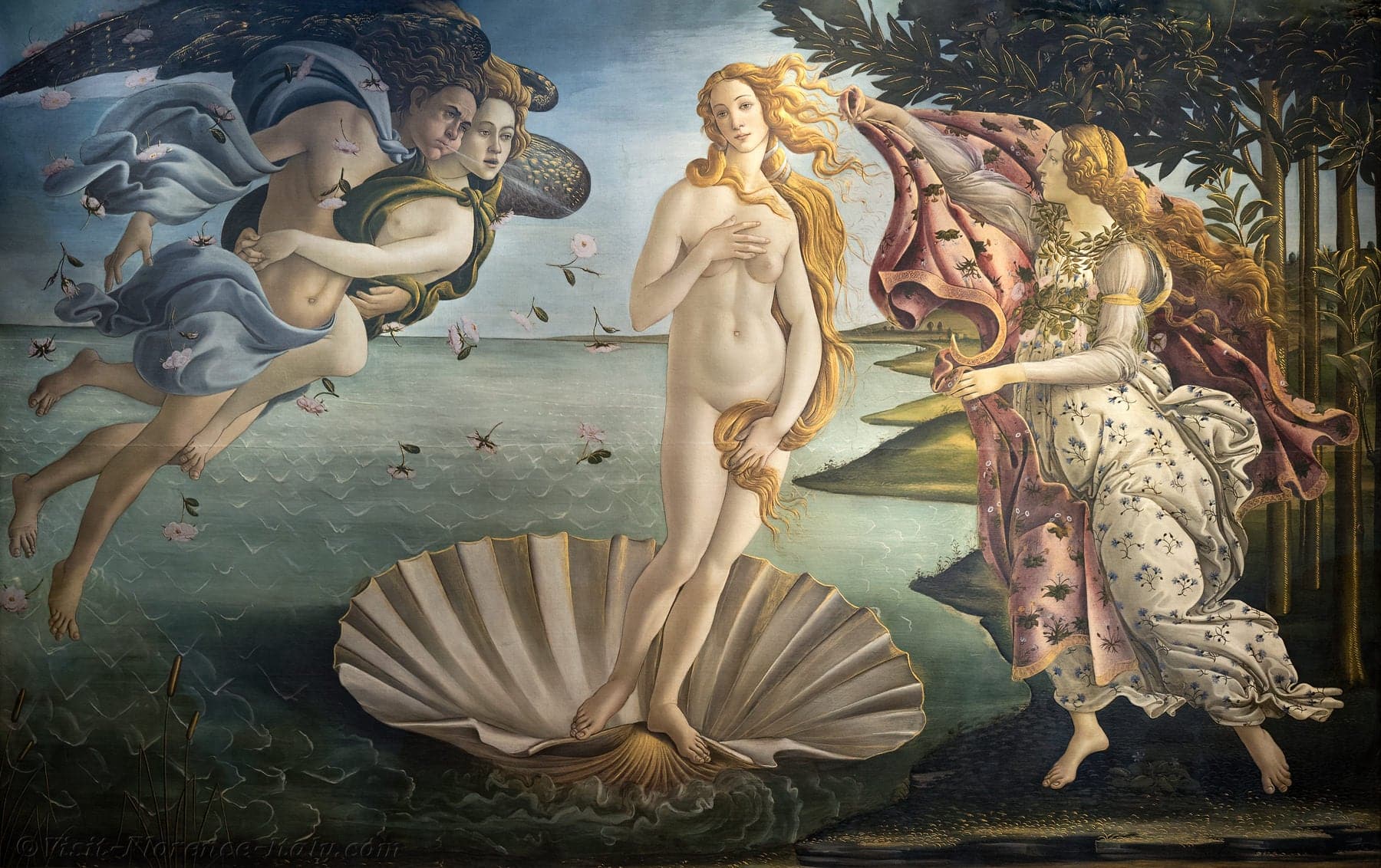

Lacan introduces the “Mirror Stage,” a developmental period occurring between six and eighteen months, during which an infant recognizes itself in a mirror. However, the infant perceives a whole, harmonious self, setting the stage for an imaginary ideal state that becomes the object of desire. The pain associated with desire stems from the yearning for a return to this impossible state of unity.

The social-symbolic order, represented by the encounter with the Other, disrupts the possibility of the desired unity, leading to a perpetual and futile pursuit of satisfaction within the realm of sexual relationships.

Lacan introduces the term “jouissance,” denoting non-pleasure enjoyment. Unlike pleasure, jouissance involves extreme excitation and intensity, existing beyond the pleasure principle. It can be associated with both inhibiting satisfaction and the transgressive edge of satisfaction itself.

Jouissance is closely tied to the “Real,” representing encounters with annihilating, overwhelming, or traumatic experiences. It poses a threat to the social order imposed through language and remains unsettling, residing beneath the surface of experiences associated with perversion and self-denial.

In the realm of psychoanalytic practice, Lacan underscores the significance of individuals recognizing their own jouissance—the terrifying and almost intolerable reality of their desires and motivations. Psychoanalysts encourage patients to confront pleasures denied and defended against through the perpetual deferral of fantasy, aiming for a deeper understanding of the complexities that underlie human desire.